It’s been years since I last wrote here. I started this blog back in fourth-year engineering while job hunting—before I joined Palantir, before robotics labs and late-night debugging sessions, before teaching, before all the twists that came after.

This week, Remembrance Day brought me back.

I had the honour of playing trumpet with our school band—not the Last Post; I’m still working to be good enough for that—but enough to stand with the group in something meaningful. Instruments in hand, everything paused for a moment, and it pulled me right back to my time in army cadets.

Even now, that first year is burned into my memory—awkward uniform, barely any badges, trying to figure out what leadership meant. Luckily we had mentors to guide us!

Cadets taught me that rank wasn’t the patch; it was the work behind it.

As we approached Remembrance Day this year, I found myself thinking about the small rituals that shaped me. Raising the flag was one of them.

Sometimes it was early, cold, or rushed—but it mattered. And I wasn’t alone.

Music also became part of those mornings, including our national anthem.

Fast-forward to high school robotics, coding, and engineering—different worlds entirely, but the same threads of discipline and responsibility ran through them.

I didn’t stay long enough in cadets to stack up badges like the mentors I admired, but the two years I spent there were full. Varied, intense, and formative, but I still loved computers.

This year, as part of preparing for our ceremony, I learned more than I expected—thanks entirely to the Student Activity Council, who did all the research.

That’s where I discovered the story of George Cardozo, one of the “Port Credit Boys.”

The Bugler They Didn’t Let Become an Officer

George’s story starts decades before mine, but strangely close to home.

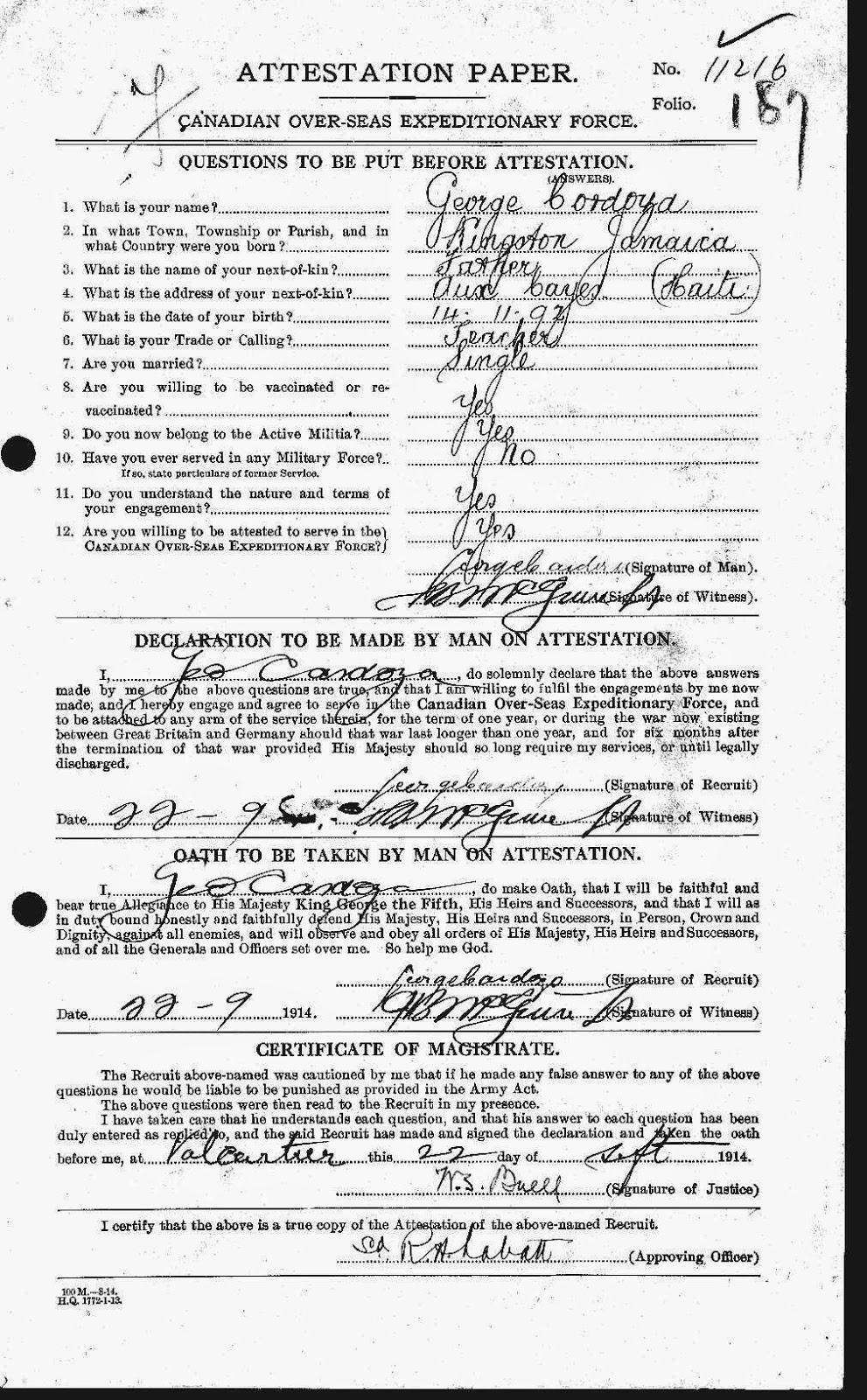

He was a Jamaican-born teacher, educated in Port-au-Prince and Kingston, who came to Canada and enlisted with the 4th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, on 22 September 1914.

One of the first recruits at Valcartier.

)

)

His attestation paper recorded only the essentials: his trade or calling, his date of birth, and his place of birth. Beyond those brief entries, the rest of George’s life, identity, and service must be reconstructed through the surviving evidence gathered from archival and family research. A fuller picture — his experiences as a Jamaican-born bugler, his movement through the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and the context surrounding his enlistment — comes from the sources compiled in the project’s research. These include My Jamaican Family’s biography They Shall Grow Not Old – George Cardozo, a Casualty of … and Remembering George Cardozo, 1890–1915, the Canadian Virtual War Memorial entry for George Cordozo from Veterans Affairs Canada, and his digitized service file in Library and Archives Canada’s Personnel Records of the First World War. Together, these sources allow us to understand George far more deeply than the minimal information captured on the photo.

According to Dorothy Kew from the My Jamaican Family Blog, he was:

- Five foot five

- Dark complexion

- “Coloured”

- Roman Catholic

- Teacher

With his education and background, he should have been an officer.

But because of his colour, he wasn’t given that chance.

Instead, they made him a bugler.

Today, the role is ceremonial.

Back then, buglers woke before everyone else, played Reveille in the cold, roused officers, and handled the morning chores no one else wanted.

George still trained hard—at Ravina Barracks, on the SS Tyrolia to England, and finally to the Western Front.

He died sometime between April 22–26, 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres—the first time poison gas was used in the Great War. His body was never found.

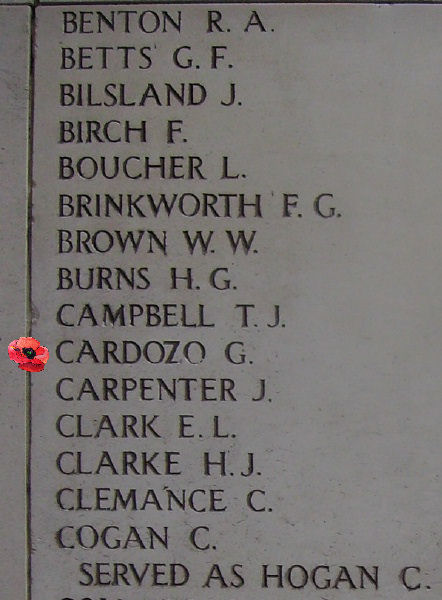

His name is carved on the Menin Gate Memorial in Belgium with over 55,000 others who have no known grave.

Every evening at 8 p.m., beneath his name, they still sound the Last Post.

Bugles, Flags, and the Things We Carry Forward

This year I raised my trumpet high,

Not for the Last Post’s mournful cry,

But with a deeper, steadier sight

Of all the threads that shaped my flight.

I thought of flags I used to raise,

The badges missed in younger days,

The mentors’ paths I didn’t tread,

And those who served and marched instead.

I thought of George—so much like me—

A teacher-learner meant to be,

Who left to fight through smoke and flame

And never made it home again.

We Remember

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old…”

— For the Fallen, Lawrence Binyon

This post is both a return and a reminder—of the past we inherit, the stories we uncover, and the unexpected ways they shape our present.

This Remembrance Day, I played the trumpet for our school.

But I also played it for George.

And I’m honoured to remember him here.